Starting coral restoration sooner or when will it be too late...?

February 27, 2018Many of us have witnessed with our own eyes the threats coral reefs are facing today: pollution and destruction of reefs, coral bleaching, the subsequent death of reefs and so on. And we know, while climate change continues to raise seawater temperatures, a coral's life is not getting any easier. Consequently, as coral cover decreases, the number of potential parents to produce new offspring for compensating the losses decreases too. This not only reduces genetic diversity of coral populations, but also, as distances between parental colonies increase, natural reproduction becomes more challenging. There are reefs in the Caribbean where some coral populations cannot reproduce on their own anymore. Active coral restoration may get more and more important to give at least some coral reefs a fighting change to see the next century.

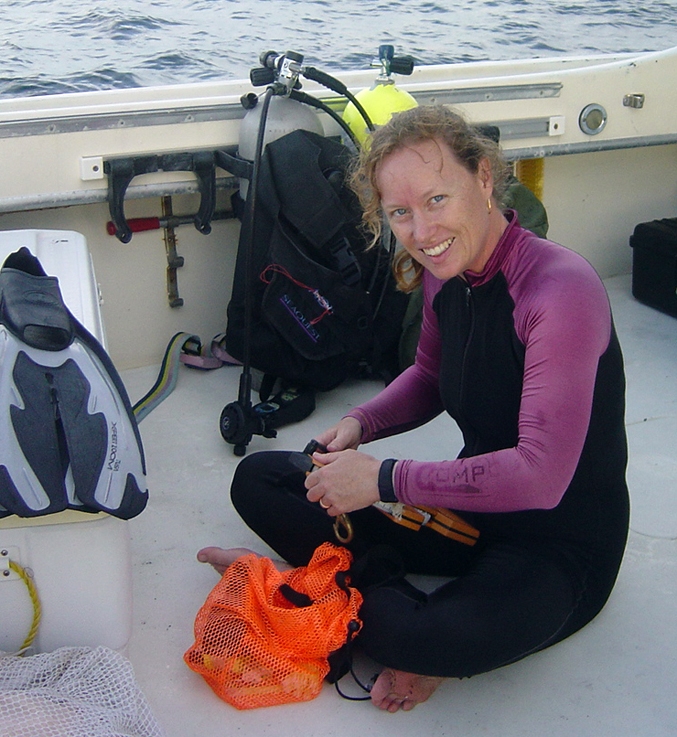

A recent study led by SECORE's Research Director Dr. Margaret Miller (published in 'CORAL REEFS') investigated this topic in the Florida Keys. Margaret Miller is a renowned coral reef ecologist who worked for NOAA ( National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S) for almost two decades before she joined SECORE last year. She is one of THE coral restoration experts in the Caribbean and is a passionate diver too, who fell in love with coral reefs when she was still a child. In the following interview Margaret Miller explains how the findings of her study affect coral restoration efforts.

Question: How are corals in the Florida Keys doing?

Margaret Miller: The reefs in the Caribbean have lost more than 90 percent of their corals in the last four decades, mostly due to thermal stress, which causes bleaching and diseases. We watch corals dying, especially in the Florida Keys, which is the worst-case area that we currently have in the Caribbean. Here the reefs are so depleted that we already have some species which are not naturally reproducing at all.

Q: How do changing environmental conditions affect reproduction of corals in particular?

MM: As we realize more and more, there are two additional reproductive challenges emerging when population density is getting very low. One of them is asynchrony in coral spawning, the other is too low genetic diversity to allow successful fertilization of eggs and sperm.

Q: Corals often spawn in so-called mass spawning nights (https://www.divessi.com/blog/magic-nights-coral-spawning-2100.html); are corals not keeping their rendezvous anymore?

MM: For coral spawning, we are talking about a time window of only a few hours, where eggs can be successfully fertilized, meaning only those individuals, which spawn in close proximity within that single night window have the potential for producing offspring. Under those conditions it becomes a real challenge for reproduction, if the few parents, which are left in a reef, spawn at different nights, as for instance the elkhorn coral Acropora palmata is known for in the Florida Keys. In this case fertilization of eggs is very unlikely.

Q: ...and corals need to be genetically different to reproduce successfully, right?

MM: Yes, to reproduce successfully, coral species such as the elkhorn coral need spawning individuals that are genetically diverse. But that is not always the case, since branching corals also reproduce through natural fragmentation. If for instance a storm hits a reef, fragments may break off from a colony, get attached to the reef right next to its parental colony and grow into a new colony. However, both colonies are genetic clones and cannot reproduce sexually. So even though I may see 50 colonies growing on a reef, it may be only one or two genetic individuals, which may prevent sexual reproduction at all. Furthermore, we were particularly interested looking into fertilization compatibility of individual parents. As you can imagine, if I only have two or three parents on a reef instead of 100, it becomes very important, if certain of those combinations are not effective in producing offspring. And that is what we investigated in this study for the Mountainous Star Coral Orbicella faveolata and the Elkhorn Coral Acropora palmata.

Q: How does this affect coral restoration efforts, in particular any concept working with sexually derived coral babies, such as SECORE’s coral restoration strategy?

MM: There are two important facts we have to consider. One is, if we restore coral populations we need to have as many parents available in a local population as we can, because not all of them are going to be successful in creating larvae. We need to fight for genetic diversity. The more genetic individuals we can keep on a reef, the higher are our chances for a successful natural sexual reproduction. The second implication is that we really want to implement coral restoration before the population gets as low as it is nowadays in the Florida Keys. Coral restoration becomes more challenging once you get to this low point where spawning synchrony or fertilization steps become added challenges. We want to keep coral populations at a level where those processes are not kicking in. Therefore we need to start restoration sooner.

Q: Does this imply that each reef manager also needs to be an expert in genetic analysis to be able to take care of the reefs?

MM: Hopefully not. If we start soon enough before the population in a certain area or reef is so depleted, it becomes much less crucial to have that fine scale information. In many of the places, for example Curaçao, where SECORE has done so much work, the populations there still are very successful and fertilization rates have been very high for many species. So, it is something to be concerned about but another reason to start restorations efforts sooner, where you don’t have to worry so much about those fine genetic aspects of our population.