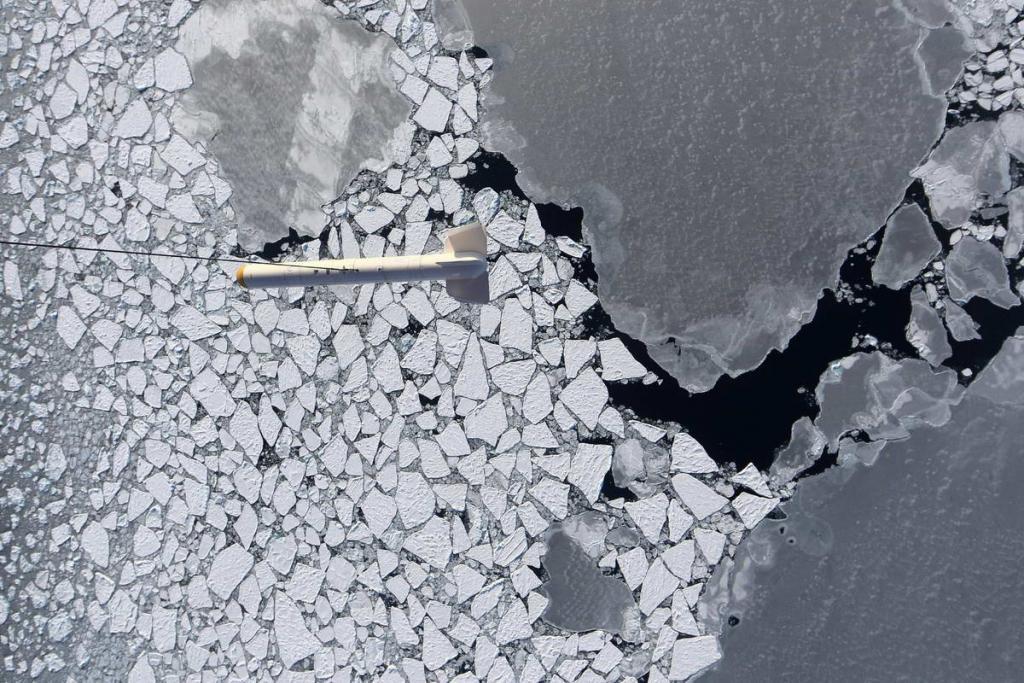

© The AWI-EM-Bird during a sea ice measuring flight over Arctic sea ice. Taking a picture of the NADIR camera aboard the research aircraft Polar 5. The photo was taken as part of the PAMARCMIP campaign in 2009. Photo: NADIR / Stefan Hendricks, Alfred-Wegener- Institute The AWI sea ice thickness sensor EM-Bird during an Arctic sea ice survey. Aerial photo taken with the NADIR camera on the German research aircraft POLAR 5. This image was taken during the PAMARCMIP sea ice measurment campaign 2009. Photo : NADIR / Stefan Hendricks, Alfred Wegener Institute (Photo: PAM ARCMIP2009)

© Snow-covered meltwater pools in the Arctic, Photo: © (Photo: Stefan Hendricks)

© Evening light in the central Arctic - here the sun shines through cloud gaps on Arctic sea ice. Evening light in the central Arctic. Here the sun is shining on Arctic sea ice. (Photo: Stefan Hendricks)

Arctic sea ice: negative record

March 12, 2018

The arctic ice cover was never smaller in a February than 2018

The Arctic sea ice is dwindling: since satellites in the 1970s have the white cap over the Arctic Ocean in view, in no single February was the area as small as this year. This is due to warm air bursts that are not only more frequent in the Arctic, but also become stronger and continue to penetrate to the north.

In February, when large parts of Europe shivered in icy polar air, mild winds from the south warmed the Arctic and brought temperatures of up to six degrees Celsius to northern Greenland in the middle of the polar night. Such summerly appearances in these latitudes with simultaneous Siberian cold in Central Europe are weather patterns that are linked to climate change. Warm air slows down the freezing of water in the Arctic Ocean. If there is less ice, the ice cover is smaller in winter than in other years and the ocean warms up faster.

In February 2018, researchers at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) actually recorded the lowest average ice surface in the far north since the satellite measurements began in 1978, at almost 14 million square kilometers. "However The ice cover in February is by no means uniform from year to year, but fluctuates considerably, "explains sea ice physicist Marcel Nicolaus from the Alfred Wegener Institute. Over longer periods, however, there is a clear trend - the ice sheet in the Arctic Ocean shrinks in February by an average of 2.75 percent per decade.

"Climate change is clearly behind this long-term decrease," says Nicolaus. With consequences for the weather of the Northern Hemisphere: As temperatures rise and the ice sheets on the Arctic Ocean shrink, the small differences in air pressure between different areas change the so-called polar jet. Meteorologists use this term to describe a belt of strong winds that roars around the globe at speeds of a few hundred kilometers per hour, high in the atmosphere from west to east. However, the Polarjet does not form a perfect circle, but can form huge loops, especially when the temperature difference between the North and the South decreases. With the climate change, the vibrations of the polar jets increase, in some places warm air penetrates much further north than in normal times, and cold air far farther south.

To better understand these changes, it is not enough to measure only the Arctic ice surface. The ice thickness also plays a significant role, because thin ice breaks faster and is easily expelled or compressed by the wind. For this reason, since 2010, researchers have measured the thickness of ice in the Arctic Ocean, mainly with the aid of the European satellite "CryoSat-2". "Here, too, a first trend to average thinner ice is emerging," says AWI researcher Marcel Nicolaus. Climate change is causing ice on the Arctic Ocean to shrink not only in surface area but also in mass. A vicious circle: the ice is becoming more sensitive and variable. This, in turn, keeps temperatures rising because open water holds much more solar heat on the earth than an ice sheet.