Invasive ctenophora: currents as a driving force

environmentmarine lifemarine ecosystemsocean currentsinvasive species

0 views - 0 viewers (visible to dev)

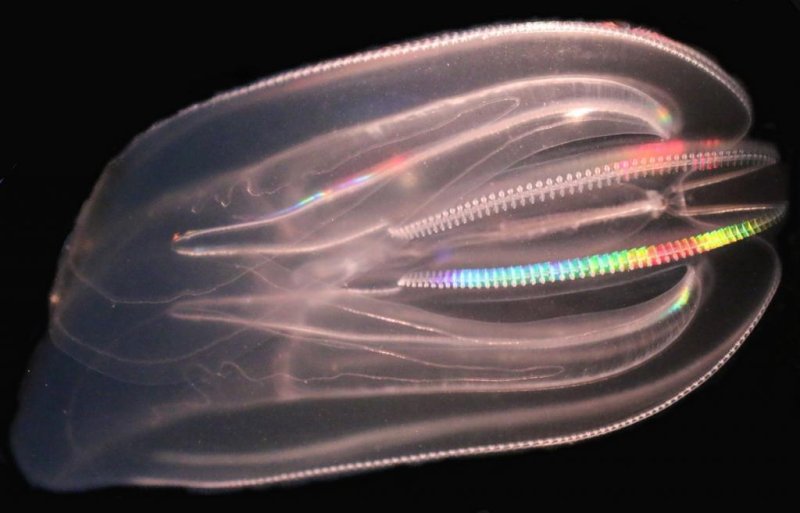

The sea walnut Mnemiopsis leidyi

(c) Cornelia Jaspers / GEOMAR, DTU Aqua

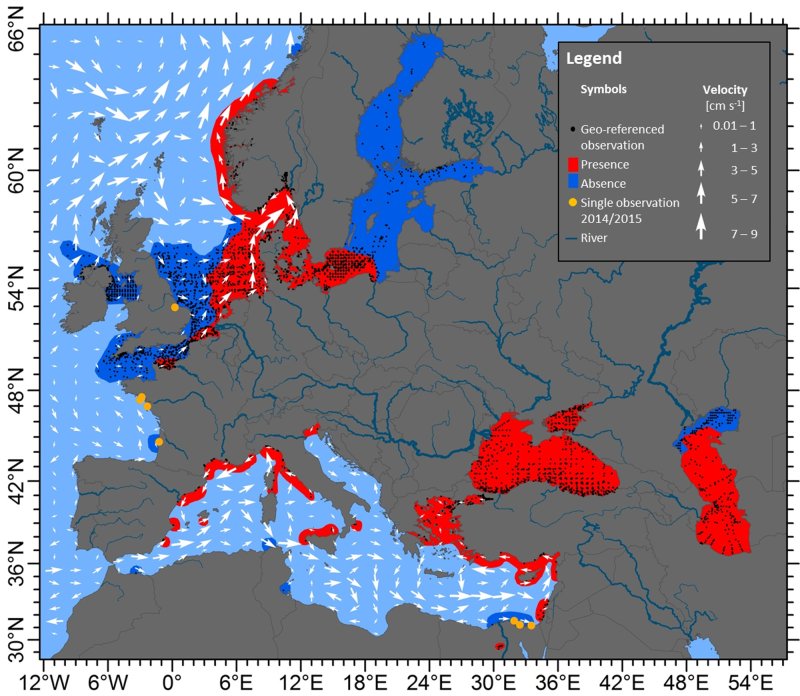

New study shows first comprehensive inventory of European crab jellyfish For 12 years, the Atlantic jellyfish Mnemiopsis leidyi, originating from the North American East Coast, has also asserted itself in northern European waters. Based on the first comprehensive data collection on the occurrence of this invasive species in Europe, scientists led by the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel have now shown that ocean currents play a key role in their success in the new habitat. 35 years ago, when the American finned jellyfish Mnemiopsis leidyi, also known as the sea walnut, conquered the Black Sea as a new habitat, it changed the ecosystem there sustainably. The economically important anchovy stocks collapsed because the jellyfish as a new food competitor made the livelihood of the fish. Against this background, science, fisheries associations and environmental authorities were alarmed when the sea walnut from 2005 also spread in northern European waters. Although similar effects in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea have not yet been observed, research is still closely monitoring developments - especially since many questions on invasive species pathways are still largely unclear. A total of 47 scientists from 19 countries published the first comprehensive inventory of Mnemiopsis leidyi in European waters in the international journal Global Ecology and Biogeography. With this data, the interdisciplinary team of authors shows that ocean currents as the pathway of invasive jellyfish and other drifting organisms in the sea have been significantly underestimated so far. "To explain the invasion of alien species in marine ecosystems, one is very focused on transport in or on ships. That's true, but it does not explain the whole phenomenon," says lead author Dr. Cornelia Jaspers, Biological Oceanographer at GEOMAR and Denmark Technical University in Lyngby. As a basis for their study, the participants have collected all the reliable data on the occurrence of American crab jellyfish in European waters since 1990 - a total of more than 12,000 geo-referenced data points. "Even this inventory is new, because so far there were only regional studies on the spread", explains Dr. med. Jaspers. In cooperation with oceanographers and ocean modellers, they linked data on the spread of Mnemiopsis leidyi to prevailing currents in European waters. The analysis included not only the flow directions and their strength, but also their stability. The models showed that the steady flow pattern of the southern North Sea closely links it with much of north-western Europe, such as the Norwegian coast and even the Baltic Sea. Due to this close connection, not only invasive jellyfish but generally non-native species floating in the sea can be spread over long distances within a very short time. "Using the imported Mnemiopsis, we were able to show that it can travel up to 2,000 kilometres within three months," says GEOMAR's physical oceanographer Hans-Harald Hinrichsen. Species that arrive in ports in the south-western North Sea, such as Antwerp or Rotterdam, reach Norway and the Baltic Sea very quickly. To confirm this connection, the authors used a natural experiment. After a very cold winter season in early 2010, the jellyfish disappeared in 2011 from the Baltic Sea and large parts of north-western Europe. It remained until 2013. But after the warm winter of 2013/14, she had immediately established again. "However, repopulation was another genotype of animals. Within a short time, a new immigration took place, driven by the prevailing ocean currents", Dr. Jaspers. Perhaps the new arrivals from the second invasion wave are even better adapted to the local conditions. Therefore, the authors argue for not only keeping track of the transport routes across oceans, but also to better investigate the possibilities of propagation within a region. "The study shows that there is a single gateway, a single port in which ships with invasive species arrive. If this port is in the 'wrong' direction in an area with strong currents, which is enough to redistribute the non-native species across entire regions." Link to the study: doi.org/10.1111/geb.12742 See also: Faster reproduction ensures success and (only available in German): Rippenquallen - Faszination und Fluch Gefräßige Leuchten der Meere

Distribution of Mnemiopsis leidyi in Western Eurasian waters for the period from 1990 to November 2016 based on 12,400 geo-referenced observations (black dots), with the areas presence (red) and absence (dark blue) marked.

(c) Cornelia Jaspers / GEOMAR, DTU Aqua