How do marine mammals avoid the diving disease?

May 3, 2018 The lung architecture of deep-diving marine mammals is divided into two partsDeep-diving whales and other marine mammals, as well as divers who emerge too quickly, can get the decompression sickness. A new study is now hypothesizing how marine mammals avoid decompression sickness. Under stress, the researchers say, these mechanisms could fail. This could explain the strandings of whales as a result of sonar noise under water.

The key is the unusual lung architecture of whales, dolphins and bottlenose dolphins (and possibly other breathable vertebrates) that show two different lung regions under pressure. Researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Fundacion Oceanografic in Spain recently published their study in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

"As some marine mammals and turtles can dive so deeply and for so long, scientists have been confused for a long time," says Michael Moore, director of the Marine Mammal Center at the WHOI and co-author of the study.

When air-breathing mammals plunge into great depths, their lungs compress. At the same time, their alveoli - tiny bags at the end of the respiratory tract collapse where the gas exchange takes place. Nitrogen bubbles form in the bloodstream and in the tissues of the animals when they emerge. When they rise slowly, the nitrogen can return to the lungs and be exhaled. But if they rise too fast, the nitrogen bubbles do not have time to diffuse back into the lungs. With lower pressure at shallower depths, the nitrogen bubbles expand in the bloodstream and tissues, causing pain and damage.

The breast structure of marine mammals compresses their lungs. Scientists have believed that this passive compression is the main adaptation of marine mammals to avoid the absorption of excessive nitrogen at depth.

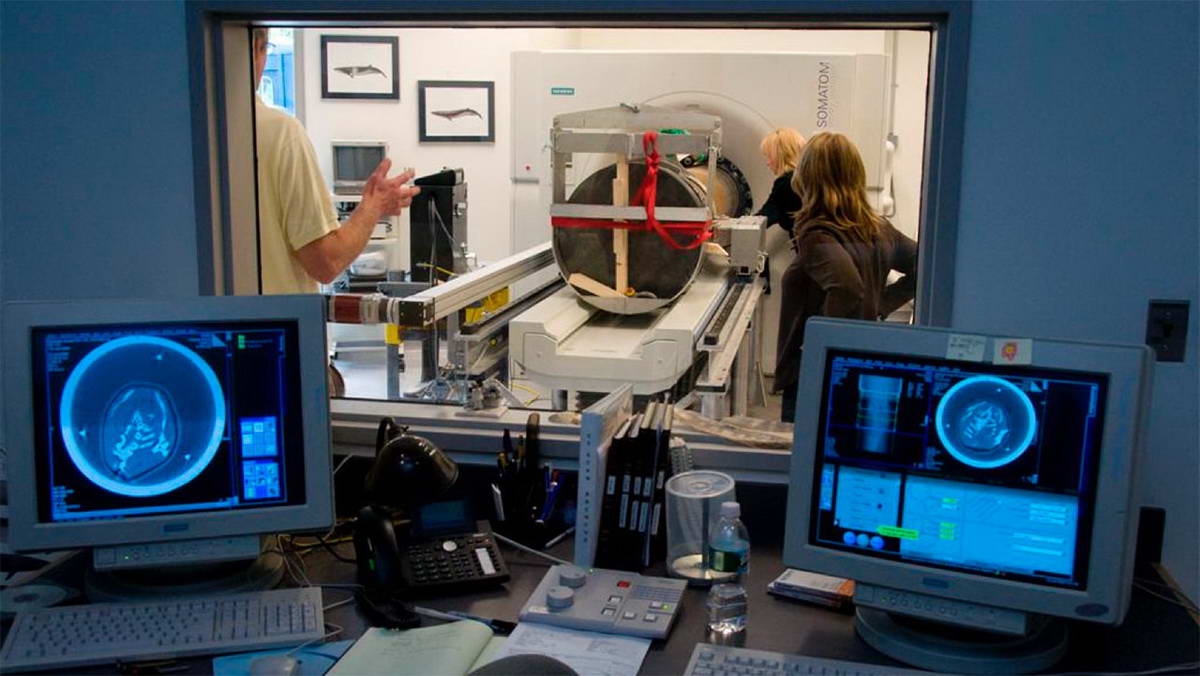

In their study, the researchers took CT scans of a dead dolphin, a seal and a domestic pig, which were pressurized in a hyperbaric chamber. The team was able to see how the lung architecture of marine mammals creates two lung regions: one air-filled and one collapsed. The researchers believe that the blood flows mainly through the collapsed region of the lungs. This results in a so-called ventilation-perfusion mismatch in which oxygen and carbon dioxide are taken up by the bloodstream of the animal while nitrogen exchange is minimized or prevented. This is possible because each gas has a different solubility in the blood. The domestic pig examined for comparison did not show this structural adjustment.

This mechanism would protect whales and dolphins from excessive nitrogen uptake, thereby minimizing the risk of decompression sickness, the researchers said.

"Excessive stress as it may occur during exposure to man-made sound can cause the system to fail and blood to flow into the air-filled regions, which would improve gas exchange and increase nitrogen in the blood and tissues when pressure decreases during ascent, "explains Daniel García-Parraga of Fundacion Oceanografic, lead author of the study.

Scientists believed that diving marine mammals were immune to the "diving disease". However, a 2002 Stranding incident associated with military sonar exercises showed that 14 whales that died off the Canary Islands after beaching had gas bubbles in their tissues - a sign of decompression sickness.

More information: http://www.whoi.edu.