© Work in the Ayalon Cave

(c) Amos Frumkin

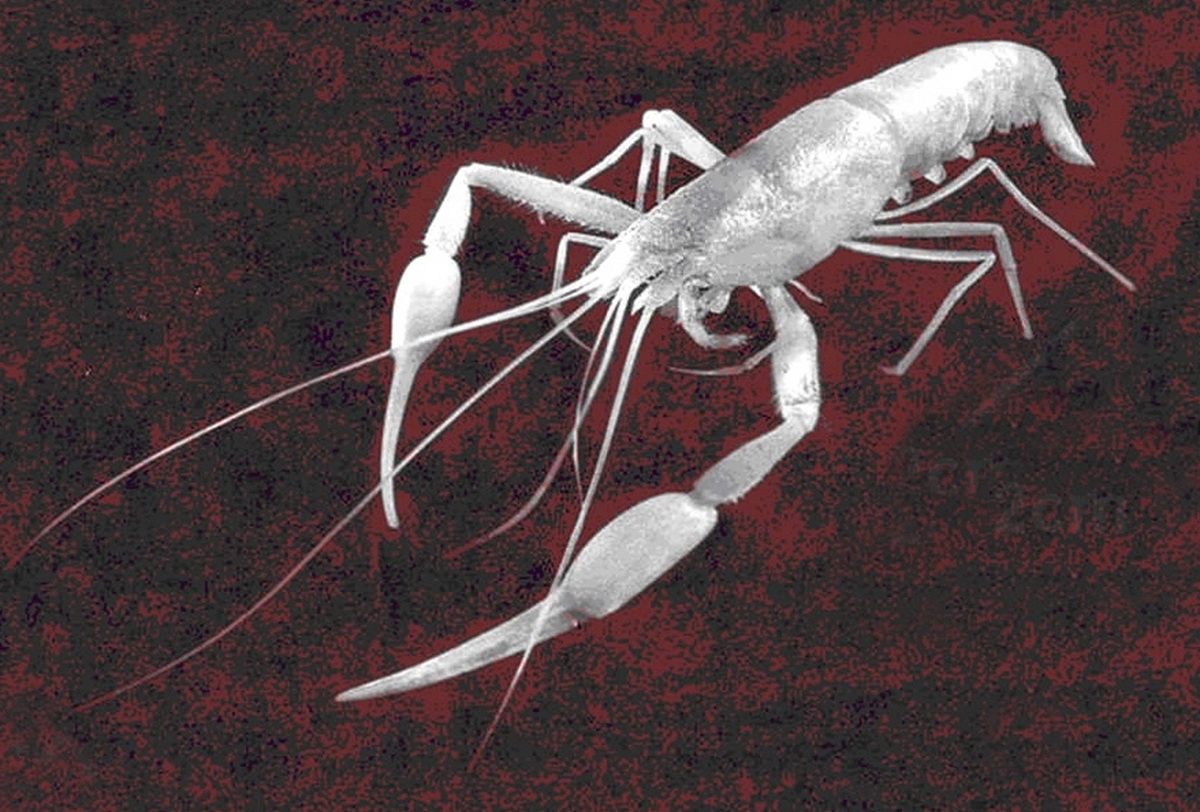

© Troglobitic shrimp Typhlocaris ayyaloni

(c) Sasson Tiram

© Typhlocaris ayyaloniin

(c) D. Darom

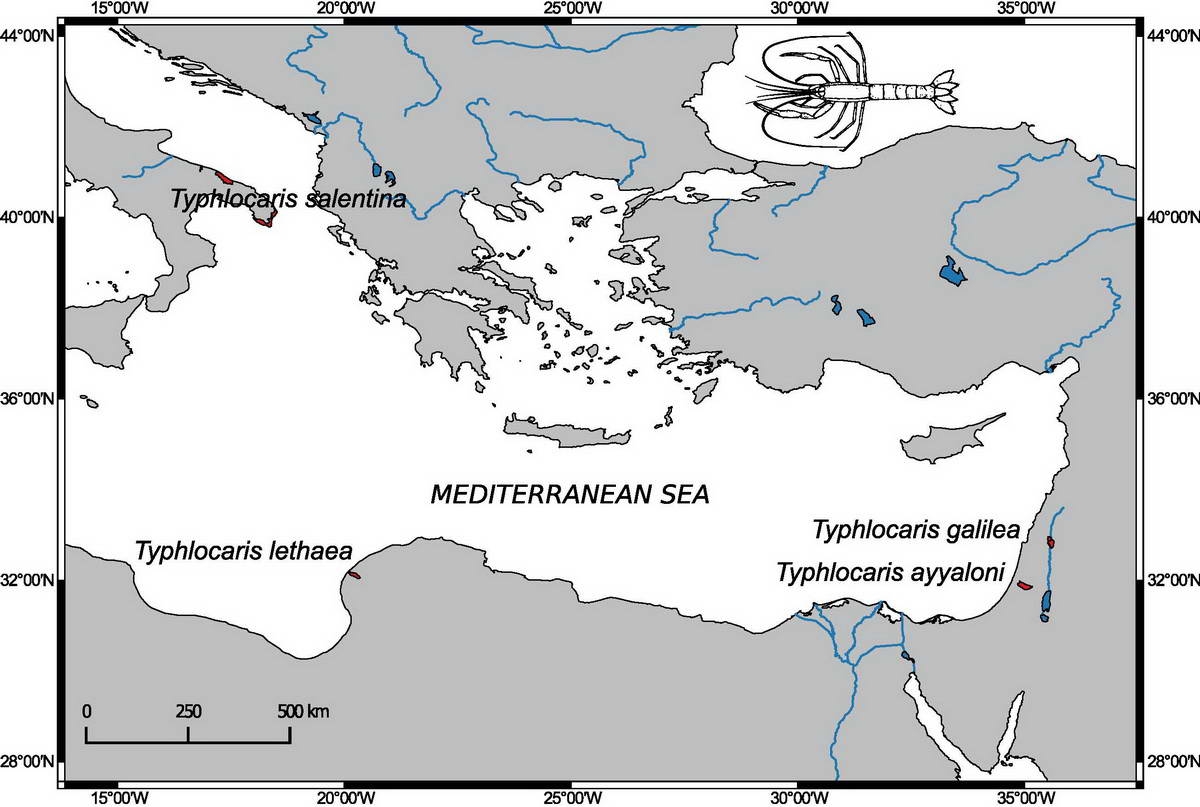

© Occurrence of Typhlocaris in the Mediterranean, map (Guy Haim et al. (2018))

Secret of the cave crabs decoded

July 24, 2018

Study shows genetic link between cave-dwelling shrimps in Israel and ItalyThe only a few centimetres large troglobitic shrimp that live in various caves in Israel and Italy, are related, although they exist isolated for millions of years. This has now been proven by a team of researchers from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel and Israeli institutions using genetic and geological analyzes.

Troglobionts live in another world - in complete darkness, with low temperature fluctuations and high humidity - a very special and secluded world in which species that have adapted to these conditions often survive long. They also include four species of the blind shrimp Typhlocaris, which can be found only in individual, karst caverns around the Mediterranean Sea. Two of these only a few centimetres large species exist in Israel - Typhlocaris galileain a cave in Tabgha, near the lake Genezareth, and Typhlocaris ayyaloniin the Ayalon cave, which was discovered in 2006 in the coastal plain of Israel. The other two species are found in a cave system near Lecce in south-eastern Italy and in a cave near Benghazi in Libya. A group of scientists has now been able to demonstrate a close relationship between the species in Israel and in Italy with the help of genetic and geological investigations. The study has recently appeared in the peerJ journal.

"The Typhlocaris species are 'living fossils', descendants of a species that existed in the prehistoric Tethys Sea millions of years ago," explains Dr. Tamar Guy-Haim, from GEOMAR and the National Institute of Oceanography in Haifa, Israel, lead author of the study. "They have since survived in isolated conditions in a unique ecosystem cut off from the outside world," continued Guy-Haim. Unlike most ecosystems based on sunlight as a source of energy for plants, these work in caves chemoautotrophically and are based on sulphide-oxidizing bacteria as a food source. The Typhlocaris shrimps are the top predators in the caves and feed mainly on small crabs, which in turn live from the sulfide bacteria.

"By comparing genetic markers, we found that one of the Israeli species, Typhlocaris ayyoni, living more than a thousand kilometers away from Italy - Typhylocaris salientina, is genetically closer than the other Israeli species, Typhlocaris galilea, which lives only 120 kilometres away," explains Prof. Yair Ahituv of Bar-Ilan University, Israel, co-author of the study.

To explain this surprising genetic relationship, the researchers dated the species divergence based on the age of a geological formation in the area of the cave in Galilee. Thus, Typhlocaris galilea was separated from the other species 7 million years ago during the uplift of the central ridge in Israel. About 5.7 million years ago, at the time of the so-called Messinian salinity crisis (MSC), when the Mediterranean was almost completely dehydrated, the Israeli species Typhlocaris ayyalon and the Italian Typhylocaris salientina diverged into two separate species.

In addition, researchers calculated the evolution rates of Typhlocaris and other cavernous crustaceans and found that they were particularly low compared to non-cave crustaceans. The researchers suggest that the unique conditions in the caves - stability of environmental conditions (such as temperature), lack of light and low metabolic rates - slow the rate of evolutionary change.

The Typhlocaris species are classified as endangered and listed in the IUCN Red List (International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources). The caves in which they live are subject to major changes due to pollution, brackish water infiltration through intensive groundwater extraction and climate change. In Israel, therefore, a breeding program for Typhlocaris was launched to preserve the kind in case all efforts fail to secure the natural population.

Link to the study: https://peerj.com/articles/5268/.