© Phronima is a crustacean that lives in the twilight zone of the ocean, where there is nowhere to hide from predators. In addition to being nearly transparent, a new study has found that these crustaceans carry an anti-reflective optical coating.

(c) Laura Bagge, Duke University

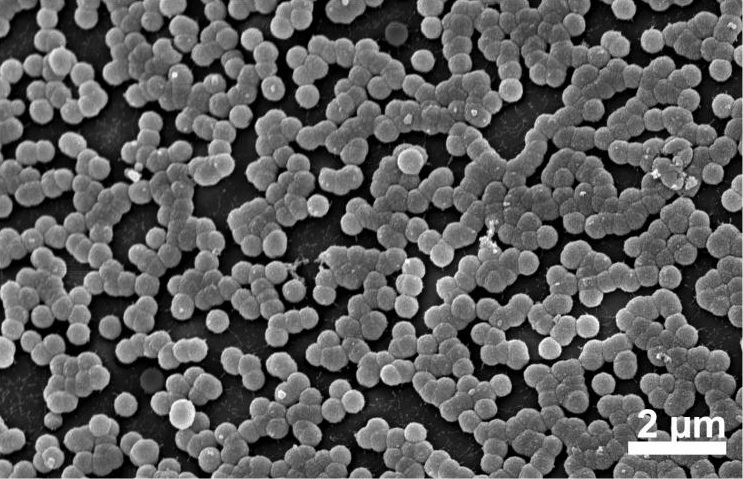

© Photos from a scanning electron microscope show the brush-like array of light-absorbing structures on the leg of a midwater crustacean called Cystisom.

(c) Laura Bagge, Duke University

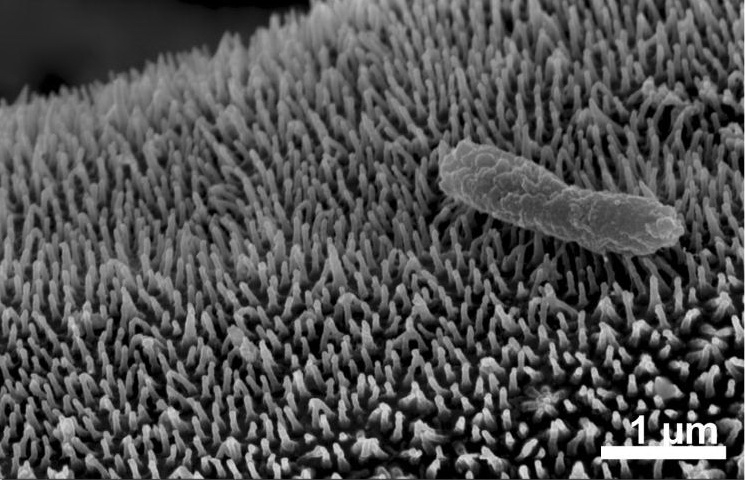

© The tiny spheres that perform the same function on the body of Phronima, another midwater crustacean. The spheres may be a colony of bacteria specific to Phronima.

(c) Laura Bagge, Duke University

Hi-tech camouflage in the ocean depths

November 9, 2016

Playing hide-and-seek in the ocean depths

A new study by Duke University and Smithsonian Institution has shown

that midwater crustaceans (hyperiid amphipods) are making use of some

pretty fancy camouflage techniques to hide from predators.

It turns out that their legs and bodies are covered with

anti-reflective coating that can dampen the reflection of light — by as

much as 250-fold in some cases — thus preventing light from bouncing

back to a potential predator.

What's more, this coating appears to be made of living bacteria.

Specifically, it appears to be a sheet of fairy uniform beads smaller

than the wavelength of light when viewed under an electron microscope.

According to study leader Laura Bagge, a PhD student at Duke

University, "This coating of little spheres reduces reflections the

same way putting a shag carpet on the walls of a recording studio would

soften echoes."

The spheres measure 50 to 300 nanometres in diameter, depending on the

species of amphipod. The optimal diameter is 110 nanometres, as this

results in a 250-fold reduction in reflectance.

For her study, Bagge worked with biologist Sönke Johnsen. They examined

seven amphipod species, and all appeared to have their own species of

symbiotic optical bacteria.

"They have all the features of bacteria,

but to be 100 percent sure, we're going to have to perform an in-depth

sequencing project," Bagge said.

If the optical coating is indeed alive, the researchers would then need to find out how this symbiotic relationship came about.

The discovery of living anti-reflective coating may have technological

application, such as in the form of reflection-reducing "nipple arrays"

which are used in the design of glass windows and are also found in the

eyes of moths, presumably to help them see better at night.